Unilife Corporation (UNIS)

A History of Missed Deadlines, Aggressive Cash Burn, and Vague Supply Agreements Suggest a 75% Overvaluation

Disclosure

We are short shares of UNIS. Please click here to read full disclosures.

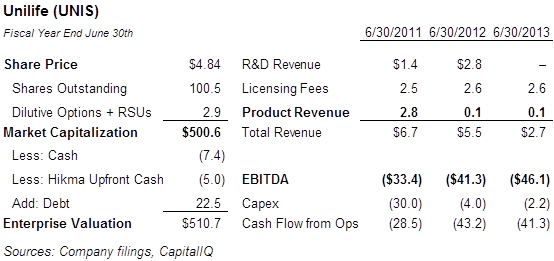

We believe that shares of Unilife (UNIS) are more than 75% overvalued as investors have once again over-reacted to deal announcements heavy on lofty potentials but light on detail. In a sequence reminiscent of the 2003 and 2009 episodic pops in Unilife’s price, shares climbed by over 50% following the announcement of a new supply agreement with Hikma. The stock appreciated a further 17% on December 3rd after Unilife reported a nebulous supply arrangement with Novartis. While the Novartis arrangement offers nothing in guaranteed revenue, the Hikma agreement promises $5m of upfront cash. Unilife is also eligible for a $15m payment in 2014, assuming certain milestones are met, and another $20m from Hikma in 2015. At a discount rate of 10%, the present value of these payments is just $35m. This is just one-sixth of the $210m market capitalization gain Unilife has realized in the days following the announcement.

The market appears to have attributed $175m, or more than $1.70/share, to hypothetical future product sales to Hikma and Novartis. Sellside analysts, whose firms are typically enriched by Unilife’s frequent share issuances, have focused on the minimum unit volume figures reported in the Hikma announcement (the Novartis arrangement doesn’t include volume targets). However, we were surprised to see that Hikma itself failed to mention specific volume targets in its own press release. Given the discrepancy, we question whether the volume targets actually represent a guaranteed revenue stream, or if instead, this is merely a minimum buying threshold that Hikma must fulfill to maintain exclusivity. We ask the question because Unilife’s volume targets for Sanofi’s Lovenox only relate to exclusivity: “After the completion of the 4-year ramp-up period, Sanofi would be required to purchase a minimum of 150 million units per year from Unilife to maintain their exclusivity” (FQ4 2013 call).

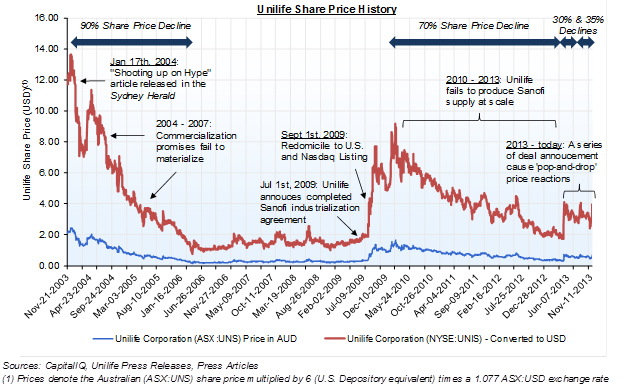

An extreme degree of skepticism is warranted because Unilife has a long history of over-promising, missing production deadlines, and disappointing its investor base. This narrative extends back to January 2004 when Unilife gave assurances that 65 million retractable hypodermic needles would be “pouring off an imported assembly line” within months. This hyped up timeline produced a tenfold increase in Unilife’s share price, a gain reminiscent to the stock’s price reaction over the past few weeks. Shareholders who bought into this story ended up losing more than 90% of their investment as the production targets were never close to being met.

In July 2009, just ahead of its 2010 Nasdaq listing, Unilife excitedly reported their industrialization agreement with Sanofi. The original press release gave a completion date of late 2010. Under this timeline, a 2009 corporate presentation from Unilife boasted about the potential for “revenues of A$400+ beyond 2014.” Today, we are five months into fiscal 2014 and Unilife’s product sales are non-existent.

If Unilife’s history is any guide, the Hikma supply agreement should not be relied upon to produce near-term product sales. Considering this, along with Unilife’s $45m annual cash burn rate, we judge the 70% jump in Unilife’s shares over the past two weeks to be a severe overreaction. This is particularly true in light of competitors that trade at much lower valuations. For example, Retractable Technologies (RVP) is a syringe business that has long marketed its VanishPoint and Patent Safe assortments of retractable needles. RVP has over $30m of legitimate product sales and yet trades at a market capitalization of just $85m. By comparison, Unilife’s $400m market capitalization on $120,000 of F2013 product sales appears flagrantly overvalued. If we optimistically believe that Unilife can match the $30m of annual product revenue earned by Retractable Technologies, we think the business would be worth 3x revenue. At this multiple, UNIS shares would be worth about $1.00, or more than 75% lower than the current price.

The Novartis Announcement

As the euphoria from the Hikma announcement began to fade, resulting in UNIS shares plummeting by almost 7% on December 2nd, 2013, Unilife felt compelled to report an exploratory-stage supply agreement with Novartis. Unlike the Hikma agreement, Novartis is not paying Unilife an upfront or defined milestone payment. If the agreement had included guaranteed economics, Unilife would have disclosed the terms as it has in past announcements.

Instead, Novartis only appears interested in testing Unilife’s syringe for a clinical-stage drug: “Under this agreement, Unilife will supply Novartis with a customized delivery device…to enable administration of a novel investigational Novartis drug into a targeted organ in clinical trials.” It seems reasonable that Novartis would test every syringe available on the market, especially for a compound still in early-stage trials. Assessing every available option in the market fits protocol and is far from a guarantee that Novartis will choose Unilife over Becton Dickinson, Covidien, or another industry leader in the future.

Unilife’s shares reacted by spiking 17% after the report before settling at $4.84 by the end of the trading day, thereby adding $70m of market capitalization. The Novartis announcement shouldn’t have surprised shareholders since Unilife reported a “Supply Agreement with Global Pharmaceutical Company” way back in November 2011. The connection is possible because the Novartis press release refers to a “development collaboration…that was commenced in 2011.” If the Novartis relationship is actually two years old, so far producing minimal returns for UNIS shareholders, then yesterday’s share price reaction appears completely unwarranted.

To put yesterday’s $70m one-day market capitalization gain in perspective, $70m is almost equal to the entire market capitalization of Retractable Technologies. It is also more than twice the amount that Sanofi paid Unilife over a four-year period for the initial industrialization agreement. This leads us to believe that Unilife’s shares trade purely on irrational exuberance without any regard for the underlying fundamentals of these contracts.

Business Overview

Unilife Corporation is a research-stage medical needle business founded in 2002 through a reverse merger into a publicly-traded shell. Unilife purports to have created revolutionary syringe designs that are differentiated from the wide range of safety needles produced by industry leaders like Becton Dickinson and Covidien. The world isn’t wanting for syringe designs; a simple search for “safety syringe” at the U.S. Patent and Trademarks Offices reveals 564 separate patents. Nonetheless, Unilife continues to tout a series of exploratory supply agreements even though the business has yet to prove it can effectively ramp production in a cost-effective, quality-controlled manner. Over the past five years, Unilife has generated just $9.4m in product revenue, all of which was derived from very basic contract manufacturing. In exchange for these meager results, Unilife has burned through nearly $200m of cash since fiscal 2006.

Viewed amongst its medical syringe competitors, Unilife appears to have little reason to exist. Unilife cannot compete with the cost, technology, and quality-control track record of the $20bn Becton Dickinson (BD) or $30bn Covidien (COV). Because syringe technology doesn’t change overnight, scale is critical to controlling costs and building a reputation for quality control. A pharmaceutical executive would be loath to risk damaging a pivotal clinical trial or damaging the safety record of a multi-billion dollar drug on a faulty needle. This makes the manufacturing prowess of industry leaders like Becton Dickinson almost impossible to replicate. One can witness the challenges of building a substantial syringe business from scratch by studying Retractable Technologies (RVP). RVP has long produced prefilled, retractable needle designs similar to Unilife’s retractable products. But RVP has been unable to surpass $40m in product sales because BD can always out-compete them on price and design quality. And yet RVP’s $30-40m of product sales dwarf what’s been generated by Unilife.

Unilife is run by Alan Shortall, a promotional CEO who peppers his language with buzz words like “game changer” and “Holy Grail” while regularly giving enthusiastic YouTube interviews and investor presentations. Dozens of articles have been penned about Unilife’s checkered past, including a 2004 Sydney Morning report on Unilife’s failed exploits in the Australian market, a 2006 article drawing attention to questionable share grants, and most recently, an October 2013 article featured in Forbes. These articles describe a management team that has repeatedly misled investors. As early as 2004, Mr. Shortall was called out by the press for his unbridled optimism. Shortall defended himself, saying, “This is not a rort, this is not a scam, we are building a legitimate business.” But nine years later, few signs of any meaningful revenues have emerged and shareholders have suffered the sorts of heavy losses endemic of stock promotions.

Unilife’s Slipping Timelines

Similar to a speculative biotechnology stock, Unilife has primarily been an equity-funded venture. Whereas the over-sized returns possible from discovering a novel, multi-billion-dollar, high-margin pharmaceutical compound might justify this funding model, it seems to make little sense for a sub-scale manufacturing business. After all, there are only so many iterations of a plunger, a barrel, and a needle that one can combine into a syringe design.

But this disconnect hasn’t prevented Unilife from leaning on an ever-morphing roster of shareholders to fund its aggressive cash burn rate. Unilife’s preferred method of raising equity is to announce a series of potential production deals just ahead of selling stock. This rhythmic sequence first began in 2002 after Unilife’s Australia-listed shares climbed to the equivalent of $13 after Shortall promised that Unilife would be producing 65m retractable needles by March 2004. After Unilife failed to reach this target and continued to burn investor’s cash at a rapid pace, Unilife’s shares crashed to below $2.00.

After Unilife’s pitch began to lose its appeal to a disillusioned Australian shareholder base, Unilife decided to take its show to the U.S. in late 2009. Just months ahead of its Nasdaq listing, Unilife stirred investor excitement again by announcing its industrialization agreement with Sanofi in July 2009. Shares quickly skyrocketed to over $8.00 as Unilife captured the imaginations of U.S. investors. But once again, after Unilife’s promises failed to materialize, shares began a multi-year decline and hit $2.50 in late 2012.

Historical insights like these are difficult to gather for two reasons: i) Unilife’s current website does not appear to archive press releases before 2008; and ii) Unilife listed itself on the Nasdaq exchange in 2009. To find history before this date, one has to go beyond SEC filings and search third-party news articles and reports filed on the Australian Exchange. We believe this historical context is important to understanding the Unilife story.

Where are the Expected Sanofi Revenues?

Long-time Unilife followers will be intimately familiar with the Sanofi partnership that Unilife has been chasing for more than half a decade. After signing the industrialization agreement in July 2009, an October 2009 article in BioMed Reports declared that commercial release of Unilife’s Unitract syringe was expected to commence in Q4 2009. Unilife was scheduled to commence production by the end of 2010 with a targeted annual capacity of “more than 40 million units” by the end of 2010. The addition of another high-volume facility was projected to be completed by the end of 2011.

Unsurprisingly, these hurdles were missed as Unilife couldn’t deliver initial supply until July 13th, 2011. Unilife’s most recent 10-Q states that Unilife continued to recognize revenue from the industrialization agreement through September 3rd, 2013. This was more than four years after signing the initial contract. But even so, Unilife continues to boast about its Sanofi relationship by recently reporting a supply contract for the drug Lovenox. Even after spending the past four and half years supposedly building out their manufacturing capacity, the Lovenox press release states that Unilife requires a brand new four-year ramp-up period. Leaving aside whether Sanofi actually needs yet another supplier of Lovenox needles, Unilife’s inability to meet their self-imposed deadlines portends continued delays in the future.

Around the same time it reported the initial Sanofi contract, Unilife was busy marketing its Nasdaq listing with a 36-page presentation. This presentation told investors that Unilife was targeting A$400m of revenue beyond 2014 with a high-production facility that could manufacture 400 million units per year. Now, just two months away from 2014, even eternally optimistic sell-side analysts can’t bring themselves to model $400m revenue targets in 2015 or 2016.

Source: 2009 Annual Meeting Presentation

The aforementioned BioMed article also reveals that Unilife relied on a Chinese distributor, Shanghai Kindly Enterprise Development Group (“KDL”), to manufacture its sharps safety products and West Pharma to manufacture seals for its needles. Strangely, these outsourced manufacturing agreements aren’t discussed in 2011 10-K filing. That a manufacturing business should be so reliant on third-party distributors should also raise eyebrows. Dependence on third-party suppliers not only impacts profits margins, it could also inhibit Unilife’s ability to scale production.

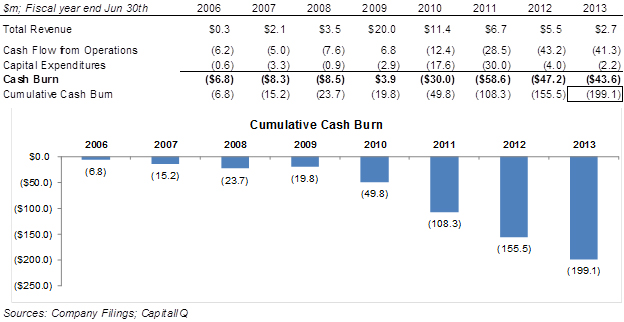

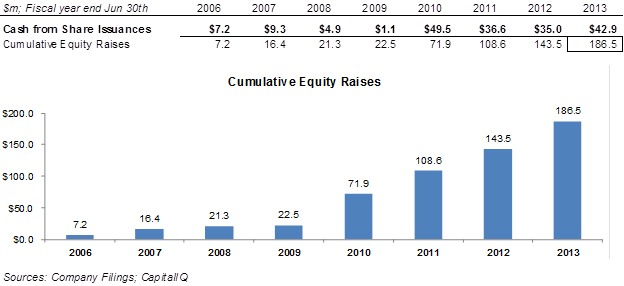

Extreme Equity Dilution: Unilife has burned through nearly $200m of shareholder cash since 2006

Lacking product sales, Unilife has instead thrived as a serial issuer of its own shares. Even after taking in $6.7m, $5.5m, and $2.7m in R&D revenue from Sanofi over the past three years, Unilife still manages to burn through ~$45-55m of cash per year. To fund this deficit, Unilife requires almost biannual secondary sales underwrote by Westor Capital and many of the coverage banks: Cantor, Jefferies, and Leerink Swan. If market conditions had been less conducive to speculative small-cap companies, Unilife might have gone bankrupt long ago.

Looking back to just 2006, Unilife’s total cash burn adds to greater than $199 million dollars. This extreme amount of cash investment has not only failed to translate into large-scale product sales, it has failed to even generate a meaningful asset base. Unilife had just $68m of total asset value as of fiscal 2013 year-end, or about one-third of the recent cash burn.

Ever-eager investment bankers have sanctioned no fewer than ten separate Unilife equity issuances since May 2006. While investors have probably lost money in each of these offerings, Unilife has made out extremely well. Secondary share sales have raised $187m for the business since 2006.

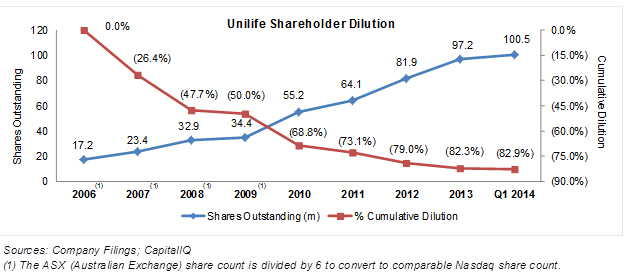

Over time, these secondary share sales would have caused approximately 83% of dilution for a shareholder that owned Unilife stock in 2006. Said another way, a shareholder that purchased 1,000 shares of Unilife in 2006 would effectively only own an ownership stake of 170 shares today.

Many of these offerings have been combined with low-cost warrants to provide a sweetener for institutional buyers. Unilife’s February 2013 offering marketed 4.46m common shares combined with 1.49m warrants set at a strike of $3.00. In these arrangements, Unilife only receives upfront proceeds on the common shares. Existing UNIS shareholders gain nothing from these warrants except for an increasingly lower economic ownership position in the business.

These cash burn figures actually underestimate the true operating expenses incurred by the business. A significant portion of executive and employee compensation comes in the form of non-cash, share-based compensation (“SBC”) expense. Unilife has incurred an additional $44m of this SBC expense since fiscal 2006.

Much of this SBC expense originates from a highly-paid executive team. The compensation packages shown below are oddly rich for a business that loses around $45m per year. Executive pay packages have included a $6.1m pay package to Alan Shortall and $6.5m for COO Ramin Mojdeh in fiscal 2012.

Source: 2013 Unilife Proxy Filing

To allow itself to sell stock more discretely, in October 2012 Unilife created a Controlled Equity Offering Sales Agreement. This unorthodox structure allows the company to sell up to $45m worth of shares for “at-the-market” (ATM) prices. The structure is typically reserved for risky companies that fail to attract an underwriting bank to manage the offering on its behalf. Since June, Unilife has issued 6.81m shares under this structure. If Unilife actually had definitive, long-term contracts in place, we see no reason that a bank wouldn’t support the business with long-term debt financing. Instead, Unilife appears to prefer continual dilution of its long-suffering shareholder base.

Conclusion

Time and time again, shareholders have underestimated the colossal difficulties in building a multi-million dollar, high-volume, FDA-approved manufacturing facility that can compete with the dominant market leader, Becton Dickinson. Some pharmaceutical companies may use Unilife to extract price concessions from other vendors, or they may be hedging their supply channels by adding a back-up partner. But we find it extremely unlikely that Unilife’s retractable needles and wearable injectors have really caught the industry by surprise. We encourage one to look at the severe price corrections Unilife experienced in 2003, 2010, and mostly recently in late-2012 to understand how the recent 70% price spike might end for new investors.

These new investors are acquiring an inordinately expensive ownership stake in a seemingly commoditized medical syringe technology. This isn’t a “game-changing” cure for a rare disease or a remarkable new carbon technology. Unilife is a basic manufacturing business that specializes in a low-cost, commoditized item.

The $210m surge in market capitalization following the Hikma and Novartis arrangements is unlikely to last. The $40m of contractual payments from Hikma, spread over the next 2 years and contingent on milestone targets, is simply not sufficiently economic to justify the subsequent 70% rise in share price. But more to the point, Unilife’s reputation as a serial diluter means that it is likely to unload fresh new shares onto the market, either by ATM or a new secondary at these elevated levels. We believe this serial stock seller could be misleading shareholders once again.

Add New Comment